The Lion of Judah is a biblical symbol representing Jesus Christ, derived from Genesis 49:9–10 and Revelation 5:5. It signifies strength, kingship, and messianic prophecy fulfilled in Jesus, who is called “the Root of David.” Historically linked to the tribe of Judah, it also appears on the emblem of Ethiopia and is central to Rastafarian beliefs. In Christianity, it affirms Christ’s authority and victory. Explore this article to uncover its deep scriptural roots, cultural impact, and enduring religious significance.

What Does the Lion of Judah Symbolize?

A Symbol of Kingship and Victory

The Lion of Judah represents dominion, royal lineage, and the fulfillment of divine promises. The lion—a creature often associated with might and sovereignty—is used metaphorically in Scripture to depict the tribe of Judah as a dominant force (Genesis 49:9). The imagery signals not just tribal power, but an expected eternal rulership that culminates in the Messiah.

Theological and Cultural Reach

In Christianity, the Lion of Judah identifies Jesus as the victorious king from David’s line. In Judaism, it points to the Davidic monarchy and tribal heritage. The symbol also gained national weight in Ethiopia, where it became the emblem of the Solomonic dynasty, representing the emperor’s divine authority. At the 1930 coronation of Haile Selassie I, the lion was central to imperial regalia and titles (Marcus, The Formative Years, 1987).

Modern Resonance

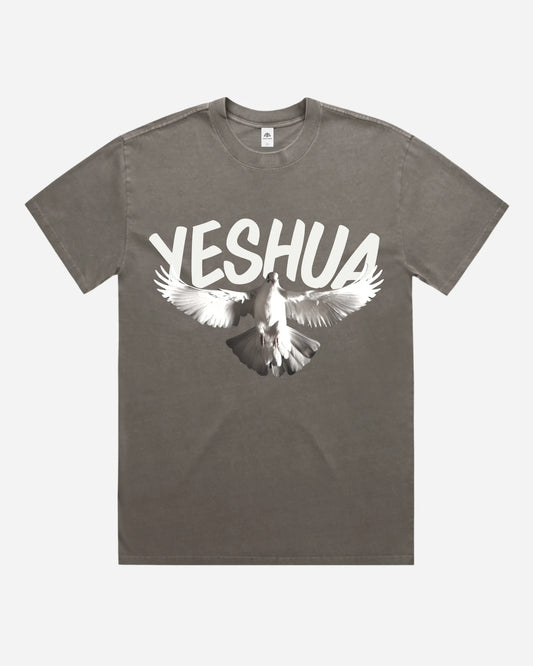

Today, the Lion of Judah endures as a cultural and spiritual icon. It appears on flags, murals, and national seals in Ethiopia and among diasporic communities. It's also popular in tattoos and Christian apparel—often paired with Scripture like Revelation 5:5 or paired with crowns, crosses, or flames. For Rastafarians, it’s chanted as a symbol of liberation and African identity. For others, it evokes personal strength, divine authority, and loyalty to Christ.

What Is the Story of the Lion of Judah?

The story begins in Genesis 49:9–10, when the patriarch Jacob blesses his sons before his death. He likens Judah to a lion’s cub, saying, “The scepter shall not depart from Judah… until Shiloh comes.” This early reference connects the tribe of Judah with leadership, power, and an enduring dynasty.

Biblical scholar Robert Alter (The Five Books of Moses, 2004) notes that this language foreshadows messianic expectations—Judah will not only lead but give rise to the ultimate ruler. This is the first appearance of “lion” language applied to Judah, establishing the symbolic foundation that Christians later associate with Jesus.

Why Is Jesus Called the Lion of Judah?

Fulfillment of Messianic Prophecy

Jesus is called the Lion of Judah because He fulfills the ancient prophecy given in Genesis 49:9–10 and is a descendant of King David from the tribe of Judah. The Gospel of Matthew opens by tracing Jesus’ genealogy through David and Judah, anchoring Him firmly in this prophetic line. The “lion” imagery represents His authority, power, and rightful claim to kingship.

In Christian theology, this title is not just symbolic—it affirms Jesus (Yeshua, His Hebrew name) as the promised ruler whose reign is eternal. His kingship is spiritual but cosmic, inaugurated through His resurrection and exaltation.

From David to Christ: The Royal Line

Throughout the Old Testament, the tribe of Judah becomes associated with leadership. David, Israel’s greatest king, came from Judah. Isaiah 11:1–10 calls the Messiah “a shoot from the stump of Jesse,” David’s father. By the time of the New Testament, first-century Jews were actively hoping for a deliverer from Judah’s line to restore Israel.

The Book of Revelation (5:5) confirms that Jesus is this deliverer—the “Lion” who has conquered. But His conquest wasn’t political or military. Instead, it came through His self-offering as the Lamb who was slain.

Lion of Judah in the Bible

Revelation 5:5 – The Lion Who Has Conquered

In Revelation 5:5, the apostle John weeps because no one is found worthy to open the scroll that unveils God's redemptive plan. Then one of the elders says, “Do not weep. Behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed.” This is the only time in the New Testament where Jesus is explicitly called a Lion, and it's loaded with messianic meaning.

Strikingly, when John looks up, he sees not a lion, but a slain Lamb. This juxtaposition reveals the paradox of Christian kingship: Jesus conquers not by force, but through sacrifice.

The lion represents strength, majesty, and the fulfillment of the Davidic kingship. The phrase “has conquered” points to Christ’s resurrection as the decisive victory over sin and death.

The Paradox: Lion as Lamb

Immediately after hearing of the Lion, John looks—and sees a Lamb standing as though slain (Revelation 5:6). This reversal is intentional. Jesus is not a predator but a sacrificial redeemer. His strength lies in His submission. As scholar Robert Mounce observed, “The Lion has conquered because He was the Lamb.”

This vision reshapes what divine power looks like. Christ conquers not by violence, but through redemptive love—turning ancient ideas of kingship inside out.

The Lion of Judah in Ethiopian History

Solomonic Lineage and the Kebra Nagast

In Ethiopian imperial tradition, the Lion of Judah symbolized divine kingship rooted in biblical ancestry. The Kebra Nagast, a 14th-century Ethiopian chronicle, claims that Menelik I—son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Makeda)—founded the Solomonic dynasty. This asserted direct descent from the tribe of Judah, legitimizing Ethiopian emperors as heirs to Davidic royalty.

The Lion of Judah, therefore, became more than religious imagery—it was the foundation of national identity and imperial theology.

Haile Selassie and the 1930 Coronation

When Haile Selassie I was crowned Emperor in 1930, the Lion of Judah featured prominently in the regalia and titles. He was called “Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God, and King of Kings of Ethiopia.” His coronation ceremonies emphasized divine legitimacy (Marcus, The Formative Years, 1987), reinforcing a sacred kingship model rarely seen in modern politics.

Flags, Coins, and Political Symbolism

The Lion of Judah was printed on Ethiopia’s imperial flag until 1974 and prominently featured on coins (Pankhurst, Economic History of Ethiopia, 1961). During the Italian occupation (1936–1941), it became a resistance symbol (Barker, The Civilizing Mission, 1968). After the monarchy was overthrown, the Derg regime abolished its use to dismantle monarchist symbolism (Tiruneh, The Ethiopian Revolution, 1993).

Broader Use in Christian Culture

Medieval European Heraldry

By the Middle Ages, the Lion of Judah had leapt beyond Scripture into Christian heraldry. Various European monarchies and knightly orders adopted lion imagery to symbolize divine kingship and Christ-like authority. This wasn’t just ornamental—it reflected theological conviction that rulers governed by divine right, echoing the Davidic model.

According to Michel Pastoureau (Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning, 1997), the lion became one of the most popular heraldic emblems because it represented courage, vigilance, and sacred kingship—all traits linked to Jesus through the Lion of Judah title.

Literary Symbolism: Aslan and Christ

In modern Christian imagination, few representations are as iconic as Aslan from The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis. Aslan is an intentional Christ figure—powerful, compassionate, and sacrificial. His resurrection in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe directly parallels the Passion narrative.

Lewis chose a lion not just for narrative impact, but because of Revelation 5:5. In Aslan, the ancient symbol comes alive for a new generation, embodying divine strength through redemptive love.

The Emblem of Jerusalem

The Emblem of Jerusalem, used by the modern municipality, features a golden lion set against a stone wall—visually recalling Judah’s tribal heritage. Though political in function, it draws deeply from religious history. As Jerusalem was historically assigned to the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:63), the lion here symbolizes continuity between biblical roots and modern Jewish identity.

Conclusion: The Lion Who Conquers

The Lion of Judah is more than a title—it’s a thread that weaves together Scripture, empire, resistance, and redemption. The Lion of Judah has conquered—not by claw or sword, but by laying down His life. That’s the paradox of Christian victory: power made perfect in sacrifice. And that Lion still reigns.