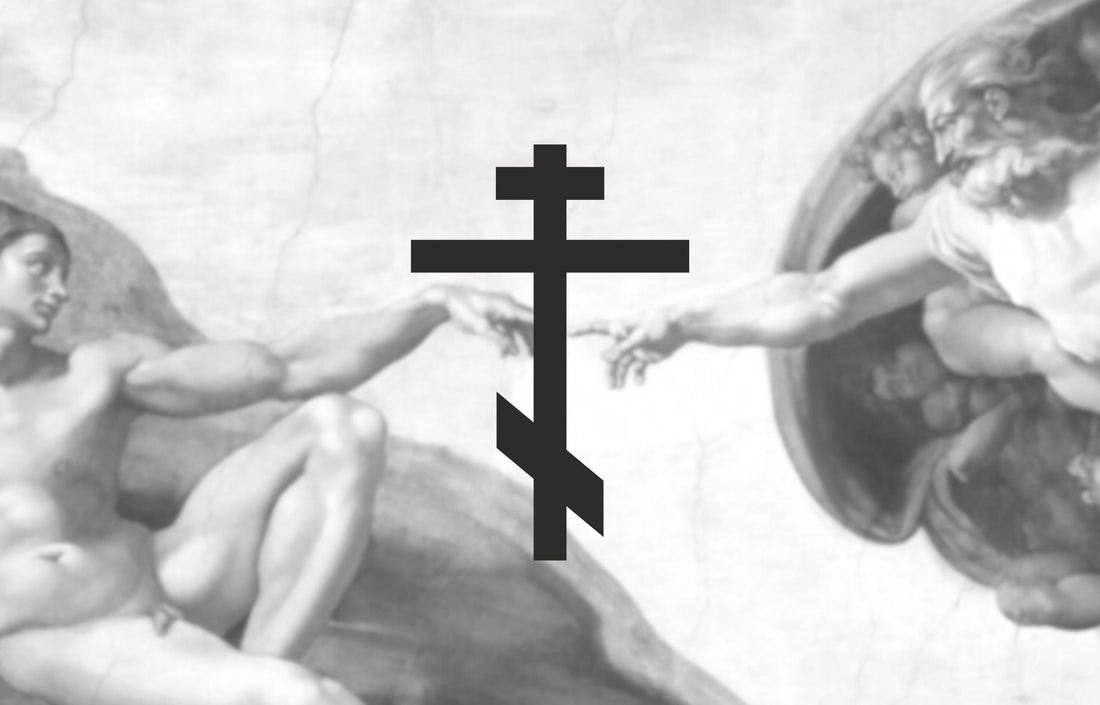

The Orthodox Cross, also known as the Eastern Orthodox Cross or Byzantine Cross, features three horizontal bars. Common in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, it dates back to at least the 6th century and remains a key symbol in Slavic and Greek traditions.

Structural Elements and Symbolism

- Top Bar: Represents the inscription ordered by Pontius Pilate, "INRI" (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews).

- Middle Bar: The main beam where Christ's hands were nailed.

- Bottom Slanted Bar (Suppedaneum): Symbolizes the footrest; its slant reflects the fate of the two thieves crucified alongside Jesus—upward towards the repentant thief (St. Dismas) and downward towards the unrepentant one.

This configuration not only depicts the crucifixion but also conveys theological themes of judgment and salvation.

Early Christian Roots and Byzantine Origins

6th Century Foundations

The three-bar design is believed to have originated in the 6th-century Byzantine tradition. Though not widespread at the time, its theological grounding was rich. The suppedaneum is referenced in early Christian apocryphal works such as the Acts of Andrew (Jensen, 2017), though its iconographic representation became standardized only centuries later.

Byzantine Cultural Influence on Slavic Christianity

The Orthodox Cross entered Slavic Christianity more definitively after the marriage of Ivan III to Sophia Palaiologina in 1472. This union linked the Russian state to the cultural heritage of Byzantium, reinforcing the importation of its cross forms (Meyendorff, 1981). Byzantine visual theology became embedded in Russian iconography and liturgical art.

The Slanted Footrest: A Symbol of Judgment

St. Dismas and the Dual Path

The slanted lower bar carries theological weight. According to Ouspensky and Lossky (1982), the upward tilt toward Christ’s right side symbolizes St. Dismas—the good thief who repented. The downward tilt toward the left reflects the unrepentant thief, offering a visual summary of divine mercy and justice.

Orthodox Interpretation

This symbolic dichotomy turns the cross into more than an execution device; it becomes a theological diagram. Salvation and damnation are visually juxtaposed in the Orthodox cruciform. The message is didactic: repentance leads to paradise, rejection to condemnation.

Regional Variations and Developments

Old Believers and the Eight-Point Cross

The 17th-century schism in the Russian Orthodox Church gave rise to the Old Believers, who preserved earlier liturgical practices. Their eight-pointed cross includes not just the three horizontal bars but additional inscriptions such as “King of Glory” above the top bar (Crummey, 2011). These variations reflect doctrinal resistance and traditionalist fidelity.

Orthodox Cross in Belarus

In Belarus, Orthodox crosses—such as the 12th-century Cross of St. Euphrosyne—demonstrate exceptional craftsmanship and spiritual reverence. Created by Lazar Bohsha, this relic embodies early Slavic Christian devotion and Orthodox visual theology (Zakrevskaya, 2010).

Orthodox Crosses in Scandinavia

Orthodox Christian influence reached as far as medieval Scandinavia. A 12th-century Byzantine-style cross found in Gotland, Sweden, illustrates the impact of Kievan Rus’ religious culture via trade and ecclesiastical exchange (Lind et al., 2004). This contradicts the notion of an isolated Nordic Christianity and shows Orthodoxy’s geographic reach.

Russian Orthodox Cross: Ecclesiastical & National Identity

Ivan the Terrible and the Russian Cross

Ivan IV ("the Terrible") solidified the Orthodox Cross as a national and religious symbol after his 1547 coronation. He merged state power with Orthodoxy, adorning churches like St. Basil’s Cathedral with the three-bar cross. His use of Byzantine-style crosses in icons and regalia reinforced Moscow’s claim as the "Third Rome" after Constantinople’s fall (1453). The cross appeared on coins, seals, and banners, symbolizing divine authority.

The Church of the Holy Spirit in Moscow

This church displays multiple cross variants, including the Slavonic cross, reflecting Orthodox theological diversity. Each design conveys distinct themes—Christ’s suffering, victory over death, and cosmic unity—serving as both a devotional and didactic symbol.

The Brotherhood of Russian Truth

This 20th-century émigré group used the Russian Cross as a nationalist emblem against Soviet atheism. Their propaganda featured the cross with inscriptions like "Golgotha" (Г.Г.) and "Paradise Be" (М.Л.Р.Б.), framing it as a symbol of resistance and cultural survival.

Liturgical and Artistic Significance

The "Golgotha" Inscriptions

Many Russian Orthodox crosses feature the inscriptions “Г.Г.” (Golgotha) and “М.Л.Р.Б.” (Place of the Skull, Paradise Be)—Byzantine liturgical elements that encode Christ’s crucifixion and victory (Sokolova, 2005).

These same phrases appear on the Great Schema, the vestments of Eastern Orthodox monasticism’s highest rank, linking the cross’s theology to ascetic devotion. Just as the cross symbolizes Christ’s sacrifice, the Schema’s embroidered inscriptions remind wearers of their call to "crucify the flesh" (Galatians 5:24) while anticipating Paradise.

The Suppedaneum in Iconography

Orthodox iconography places high importance on the suppedaneum. Though textual references exist in early Christianity, standardized visual depictions of the slanted footrest became common only after the Byzantine period (Jensen, 2017).

Orthodox Church Cross as a Symbol of Resistance

The Ottoman Occupation

During Ottoman rule, the three-bar Orthodox Cross became a covert symbol of resistance. Restricted in public worship, Christians etched it into home altars, garments, and church art to preserve identity under Islamic dominance (Roudometof, 2001). In Greece, Serbia, and Macedonia, it appeared in folk art and grave markers, maintaining Orthodox defiance even as churches were converted.

The Cross in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Despite the state’s pagan (later Catholic) rule, Orthodox communities in Slavic territories (e.g., Belarus, Ukraine) used the three-bar cross to assert Eastern Christian identity against Catholic influence post-Union of Krewo (1385). Monasteries in Polotsk and Smolensk preserved Byzantine-style crosses, aligning with Kievan Rus’ and Muscovy as Orthodox power centers.

Archaeological and Historical Rarity

Crosses from the Principality of Polotsk

The Cross of St. Euphrosyne (12th century), a jeweled reliquary made by Lazar Bohsha, remains one of the finest examples of early Slavic Orthodox craftsmanship. It served both a devotional and national purpose and was revered as a relic in Belarus. While the original was lost during WWII, its replicas are considered sacred and scholarly treasures today (Zakrevskaya, 2010).

Pre-Mongol Crosses

Few Orthodox crosses from pre-Mongol Rus’ survive today due to extensive destruction during the Mongol invasions. Examples like the Novgorod crosses are rare and archaeologically significant (Pushkina, 2003). They offer a window into the liturgical life of medieval Eastern Slavs.

Viking-Byzantine Cross Hybrids

Archaeologists in Scandinavia, particularly on Gotland, have discovered 12th-century crosses bearing strong Orthodox (Byzantine) influence. These were likely traded or brought through contact with Kievan Rus’, illustrating early intercultural exchange between the Orthodox East and the Norse world (Lind et al., 2004). The presence of the three-bar design in these regions demonstrates the wider geographical spread of Orthodox iconography.

Balkan Monastic Crosses

In remote Balkan monastic sites dating to the 14th and 15th centuries, researchers have found Orthodox crosses carved into cave chapels, stone iconostasis, and wooden liturgical objects. These were often hidden during Ottoman rule, which makes their survival particularly rare. Some feature the slanted suppedaneum and Golgotha inscriptions, linking them to resistance-era iconography.

Crosses in Global Orthodox Practice

Ecumenical Patriarchate and Unity

As the leading see of Orthodoxy, the Ecumenical Patriarchate promotes the three-bar cross as a unifying symbol across jurisdictions. It emphasizes the cross’s theological and liturgical significance in councils, encyclicals, and global events—from Greece to diaspora communities. During post-Communist reconciliation and ecumenical dialogues, the cross has served as a visual reaffirmation of shared Orthodox identity.

Czech and Slovak Orthodox Churches

Officially autocephalous since 1998, these churches have reclaimed the Orthodox Cross after Communist suppression. Restored churches in Prague and Prešov feature the three-bar cross, linking their faith to Saints Cyril and Methodius’ 9th-century mission. The cross appears in processions and festivals, blending theological and cultural revival.

Queen Tamar of Georgia

During her reign (1184–1213), Tamar made the Orthodox Cross a symbol of divine kingship and national unity. She commissioned churches and monasteries featuring the cross in frescoes, coinage, and military banners, aligning Georgia’s Golden Age with Byzantine imperial ideology. Georgian chronicles depict her as a theologically ordained ruler.