I Can Do All Things Through Christ Who Strengthens Me: Understanding the Origin and Context of Philippians 4:13

I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13) is one of the most quoted verses in Scripture. Written by the Apostle Paul around AD 61–63 during his Roman imprisonment, the statement emphasizes endurance in hardship rather than unlimited achievement.

Far from a motivational slogan, it is a confession of resilience rooted in Christ. This article unpacks its biblical context, theological meaning, and cultural legacy.

The Biblical Origin

Philippians 4:11–13

11 Not that I speak in respect of want: for I have learned, in whatsoever state I am, therewith to be content.

12 I know both how to be abased, and I know how to abound: every where and in all things am instructed both to be full and to be hungry, both to abound and to suffer need.

13 I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me.

The Verse in Context

Philippians 4:13 concludes Paul’s reflections on contentment in Philippians 4:10–13. He thanks the Philippians for their financial support but stresses his joy is not tied to material provision.

He has “learned the secret of being content in any and every situation…whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want” (Phil. 4:12). The statement of strength in verse 13 flows from this testimony of resilience (Thielman, Philippians, 2022).

The context is not triumph in competition or prosperity, but endurance in need and hardship. The surrounding verses anchor this meaning clearly.

Original Greek Meaning

The Greek text reads: panta ischyō en tō endynamounti me Christō. The verb ischyō means “to be strong, endure, prevail,” while endynamounti (present participle) means “the one continually strengthening me.”

A closer translation is: “I have strength for all things in the one who continually empowers me, Christ” (Fee, Paul’s Letter to the Philippians, 1995).

The verse describes an ongoing relationship of empowerment, not a one-time infusion of power. It testifies to constant reliance on Christ.

Historical and Theological Background

Paul’s Prison Epistles

Philippians belongs to the “prison letters” (Philippians, Ephesians, Colossians, Philemon), written while Paul was confined in Rome (Acts 28:30–31). Around AD 61–63, Paul lived under house arrest, chained to a Roman guard. Despite his restricted condition, Philippians radiates joy, with “joy” and “rejoice” appearing more than 16 times.

Paul’s declaration in 4:13 is therefore striking: it was written not in victory but in captivity. As Bockmuehl (1998) notes, it reflects how divine strength sustains believers in suffering.

Early Church Reception

Church Fathers consistently read Philippians 4:13 as Christ-centered dependence. Chrysostom (c. AD 349–407) wrote that Paul shows “the sufficiency of Christ, not of himself.” Augustine (354–430) saw in it the working of grace: “For without Him we can do nothing.” This interpretation provided courage for persecuted Christians across the Roman Empire.

Misuse and Misinterpretations

The Prosperity Gospel Reading

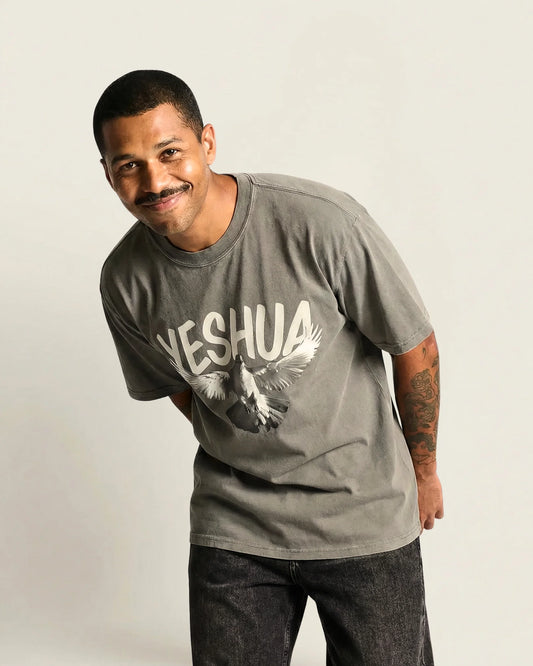

Modern prosperity preaching often seizes on Philippians 4:13 as a promise of material success or athletic victory. It is one of the most cited verses in American sports culture, often inscribed on jerseys, tattoos, and eye-black strips by athletes (Hoffman, Good Game: Christianity and the Culture of Sports, 2010). However, biblical scholars almost universally reject this reading (Bowler, Blessed, 2013).

The Real Message

Paul himself endured beatings, hunger, and shipwrecks (2 Corinthians 11:23–28). His “all things” included these hardships. The verse rejects triumphalism and instead affirms Christ’s power in weakness (Hawthorne, Philippians, 2004). To turn it into a self-empowerment slogan is to strip it of its cruciform depth.

Unique Perspectives

Psychological Angle: Contentment and Resilience

Paul’s teaching aligns with resilience theory in modern psychology. Research on “religious coping” shows that believers who interpret hardship through faith experience better emotional outcomes (Pargament, The Psychology of Religion and Coping, 1997). Paul’s contentment (autarkeia, Phil. 4:11) echoes Stoic ideals but transforms them. For Stoics, sufficiency came from inner willpower (Seneca, Letters). For Paul, sufficiency comes from Christ (Engberg-Pedersen, Paul and the Stoics, 2000). This Christ-centered resilience offers hope beyond mere self-discipline.

Linguistic Insight: “In Christ” Formula

The phrase en Christō (“in Christ”) occurs more than 80 times in Paul’s letters (O’Brien, Epistle to the Philippians, 1991). It is a theological shorthand for union with Christ in life, death, and resurrection. Philippians 4:13 reflects this pattern: strength comes not from human capacity but from being “in Christ.”

Liturgical and Devotional Use

The verse has been woven into Christian liturgy and devotion. The Catholic Liturgy of the Hours includes Philippians in its daily cycles. Orthodox spirituality interprets it through the lens of theosis—participation in divine life. In Protestant devotion, it is frequently cited as encouragement to persevere. Its memorization rate remains high: the American Bible Society (2023) ranks it among the top 5 most-shared verses in the U.S.

Lessons for Today

Strength in Weakness

For modern believers, Philippians 4:13 offers a theology of survival in crisis. It speaks to those battling illness, unemployment, or grief. Studies in psychology of religion affirm that interpreting suffering through faith reduces stress and increases resilience (Pargament, 1997). Paul’s testimony invites readers to embrace weakness as the very space where Christ’s power is revealed (2 Corinthians 12:9).

Shaping a Christian Work Ethic

The verse also shapes Christian vocation. Rather than fueling unchecked ambition, it cultivates humility and perseverance. Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) shows how biblical teaching on diligence influenced Western labor culture. Philippians 4:13, rightly understood, supports perseverance but tempers it with dependence on grace.

Hope in Cultural Context

In American history, the verse has provided hope in public struggles. It was often cited in the Civil Rights era to sustain endurance against injustice. Its popularity in tattoo culture and sports underscores its inspirational power, though often detached from context (Kosut, Encyclopedia of Gender and Society, 2009). Scholars caution against reading it through the lens of American individualism, which can distort its communal and Christ-centered message (Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God, 2013).

Comparative Theological Perspectives

Catholic Interpretation

Catholic theology interprets Philippians 4:13 within the doctrine of grace and the sacraments. Aquinas cites it in his discussion of infused virtues (Summa Theologica I-II, Q. 109). Grace enables believers to act beyond natural strength, echoing Paul’s dependence on Christ.

Orthodox Interpretation

Orthodox thought links the verse with theosis. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359) explained that divine energies empower believers for endurance. Philippians 4:13 becomes a testimony of ongoing participation in divine life.

Protestant Interpretation

For Martin Luther (1483–1546), Philippians 4:13 reflected justification by faith: the Christian endures suffering not by works but through Christ’s righteousness. Contemporary Protestant devotion often highlights the verse as encouragement in discipleship and service.

Conclusion

Philippians 4:13 is not a promise of worldly victory but a confession of strength in weakness. Written from prison around AD 61–63, Paul’s words model resilience in Christ, not self-empowerment. Early Fathers, Reformers, and modern scholars alike affirm its meaning: divine sufficiency in hardship. For believers today, it offers a profound alternative to triumphalism—a framework of endurance, humility, and hope.